By Michelle Armstrong-Spielberg and Cordelia Jones

The object we studied was an 80x75cm story cloth describing Hmong people’s escape from Laos in the 1970s and 1980s. The object was donated to the East Side Freedom Library by Karen James, a woman who received it as a gift from a Hmong family she helped settle in North Carolina that later moved to the Midwest. The story cloth was made by hand in May 2007 and therefore is in good condition with only a few loose threads.

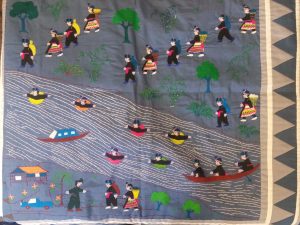

The cloth follows the Hmong’s escape from the top of the cloth to the bottom. However, it is unclear whether the events are happening at the same time or in a linear progression. At the top of the cloth, people are coming down from the mountains. In the middle, they are floating down and crossing a river. At the bottom, they are arriving in Thailand and being driven to a village. Although it seems like these events are happening in sequence, there is no clear temporal delineation. All of the figures on the story cloth have similar features and clothing, so it is hard to tell if the people featured in each section of the cloth are members of the same group or different people at different phases of their escape. The sequence of the story zig-zags, as the viewer’s eye follows the movements of the people and the flow of the river from the top right to the bottom left.

We noticed a few patterns across the story cloths we viewed. Other story cloths describe similar escape experiences and explain why and how the Hmong left Laos. One, for example, pictured explosions, shooting, and more graphic violence and showed people escaping by airlift. The story cloths also had similar blue-green color schemes and nearly identical borders consisting of repeating triangle patterns in contrasting colors.

The creator of the story cloth, likely a Hmong woman, has agency because the cloth allows them to tell the story of what is likely their own escape from Laos. This object’s purpose was to share information, namely the cultural and historical memory of this escape. The women who likely created the story cloths acted as specialists entrusted with the duty of enforcing collective memory by recording and passing down their stories. This master storyteller has the collective memory of the Hmong people escaping from Laos at the end of the Vietnam War. Most Hmong immigrants have the authority to tell this story because it was their lived experience. However, the multiplicity of histories during this time, as shown by the many story cloths created, further contributes to the shared refugee experience.

Story cloths are similar to other forms of visual, written, and oral storytelling such as the Lakota Winter Counts and Beowulf. The Lakota Winter Counts were like a calendar in that they tracked the passing of time. Like the story cloths, the Winter Counts only used images to describe what happened. Because they were used like a calendar, only one picture represented an entire year. With the story cloths, however, the whole cloth represented a single significant event. The format of the story cloths is also similar to that of sagas such as Beowulf. The story cloths, like Beowulf, communicate and share the collective history of a people using the format of story, although they are less fantastical and depict events from more recent memory.

Visiting the East Side Freedom Library allowed us to interact with forms of historical texts that are traditionally undervalued or outright dismissed. This alternative text can still be used to document historical events and provide valuable insight into social history and cultural memory. In looking at the story cloths as a collective, we can discern the multiplicities of experiences among an ethnic group.

You must be logged in to post a comment.