Rena Zhang and Nathaniel Lay

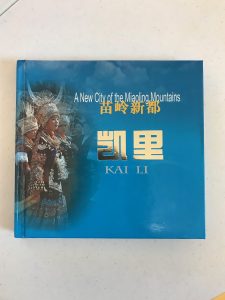

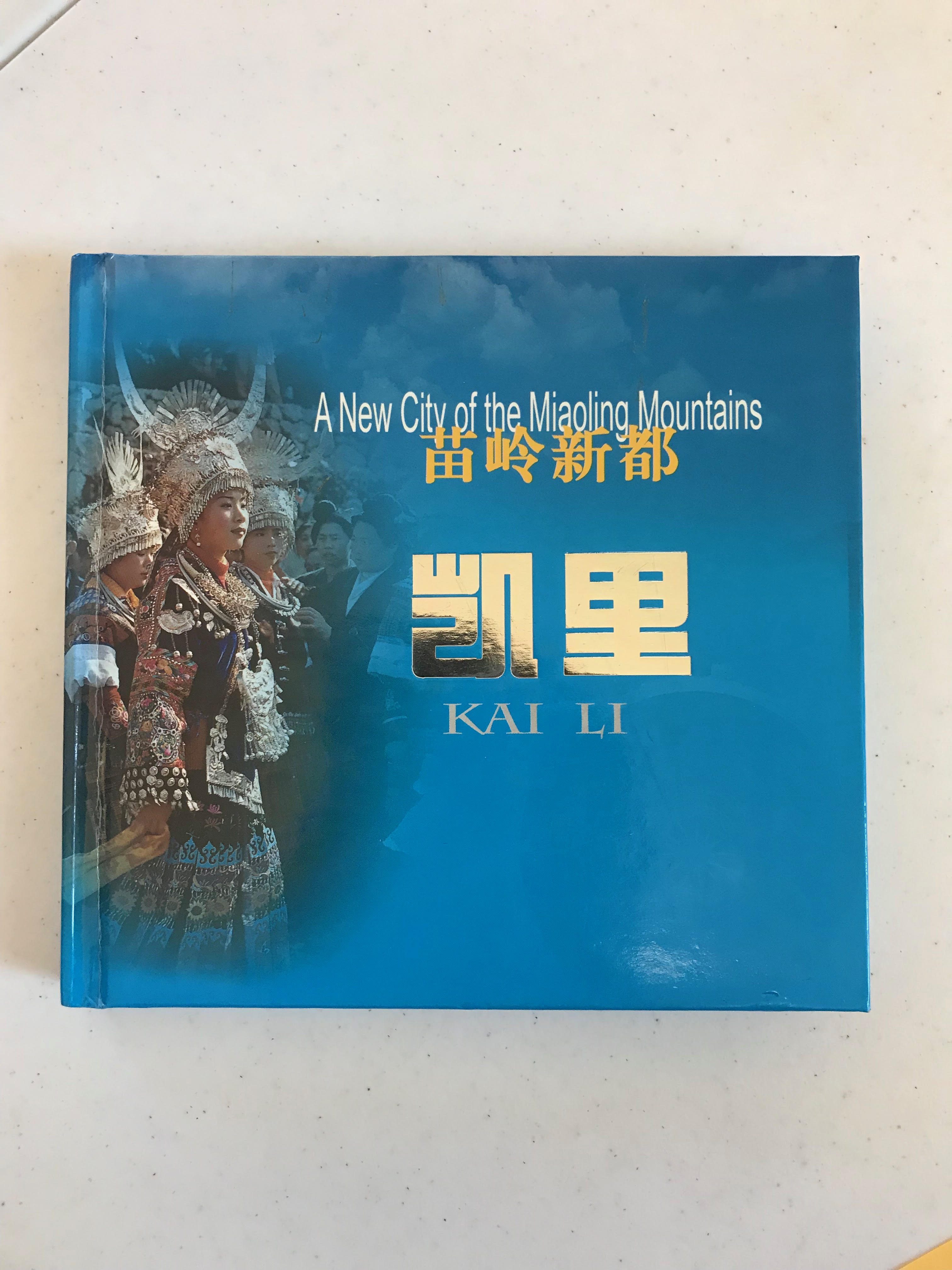

For our object analysis I and Nathaniel investigated a palm-sized, hard-cover travel guide

donated to the East Side Freedom Library in 2002. The guide introduces the town of Kaili in Guizhou Province, China, which is home to a large number of Chinese Hmong (Miao) people. Using bilingual (Chinese-English) text and color photographs, it describes the culture, festivals, handicrafts and fashions of the locals, as well as the region’s scenic landmarks and natural resources. The guide is in quite good condition and was published by Sinon Printing co. Guessing from the quality of the binding and printing, we think it is probably mass-produced.

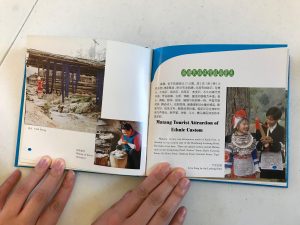

The main purpose of this 95-page guide is to promote ethnic and natural tourism of Kaili. Right from the beginning, it introduces Kaili as one of ten locations designated as “return to the simplicity of nature” sites, and uses florid language to paint an extremely romanticised portrait of its people and landscape. Here, the Hmong are colorful, passionate and pure, their musical festivals a dazzling cacophony of joy, their surroundings removed from the rat-race of the cities. There are a lot of images focusing on the distinctive attire of the women, a theme which I have seen in a lot of other images promoting ethnic tourism. The guide also places strong emphasis on the various events held in Kaili, advertising them to its Chinese and English-speaking audience. It tells us of an ethnic tourism trend in China which romanticizes and incorporates ethnic minorities like the Hmong into a narrative of collective nationalism and nostalgia.

As such, the “story” this guide tells is one of timelessness, where the Hmong seem forever idealized and unchanging. There is little acknowledgment of their lived realities, which serves an overall narrative about returning to simpler, more natural times. Alongside this narrative is another one which promotes the common Chinese notion of unity among ethnic groups–the Hmong are referred to as “tongbao”, a term which roughly means “compatriot” or “kin/fellow”. This term has been commonly applied to other ethnic minorities in China that are not Han. The end product is a strange mix of capitalism (in the form of ethnic tourism) and nationalism which presents large silences regarding how the Hmong of Kaili actually live and react to the larger context around them.

We determined that whatever institution in charge of devising and publishing the book had the agency in this case. Although we found an official publishing company listed in the book’s cover, we surmise that its creation was ordered and supervised by the local city or provincial government, which would’ve definitely had an interest in promoting ethnic and natural tourism for the region. The writer we identified, Wang Qiao, must have been complicit in the system of narrative-making and power promulgated by this government, resulting in the extremely romanticizing language meant to attract visitors (and revenue) to Kaili.

We compared the way this guide “tells history” to some of the ancient ways of telling history we have previously studied, such as the Epic of Sundiata and Bede. While the ancient histories have a strong didactic bent, endeavoring to portray historical happenings as teachable moments about cultural values, the guide has an agenda that is more geared towards advertisement and the attraction of visitors to the specific location it describes. It does espouse some values, such as the notion that some places and times are more “natural” and “ideal” than others, or the notion of unity between ethnic groups in China, but these are subsumed under the main agenda which seeks visitors and profit. This made us reflect on the gulf between these histories’ time periods, on how in ancient times there was no notion, at least in the modern sense, of “tourism” and the industry associated with it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.