P9.2005.110/UNK/ Donated by Charlotte Prentice (P9), a public school teacher, to the East Side Freedom Library in Oct. 2005. Created by unknown maker.

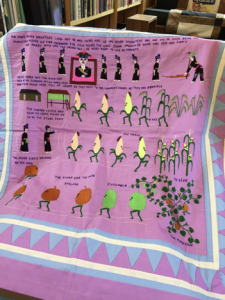

The story cloth I examined depicts a Hmong folk tale about a king’s daughter. The upper quarter of the cloth shows the king with his seven daughters, the youngest of whom marries a poor orphan. The rest of the cloth shows the daughter and her husband as farmers. Around them, rice, corn, pumpkins, cucumbers, and other vegetables march in a procession towards their barn for the harvest. Hand-lettered words caption the events in shaky English. The acquisition sheet at the library did not record who made the cloth or when, but it was acquired in 2005 from a retired schoolteacher named Charlotte Prentice.

This story cloth uses a combination of beautifully embroidered images and hand-lettered words. This is significant because not all of the story cloths have written words on them, and this one has words in English. According to the acquisition sheet, it used to have a label that read “Early efforts to learn and use English in Hmong sewing.” The content of the cloth – a folk tale – and the fact that it was written in English suggest that it might have been meant to help both the storyteller and the listener learn the language by means of a familiar story.

The passage of time on the story cloth is presented in a way that suggests its use as an aid for verbal storytelling. There seems to be a narrative gap between the king’s youngest daughter marrying and the harvest occurring. It is likely that there was a verbal part of the story told between the marriage and harvest images that we don’t get to see because the cloth is divorced from its storyteller.

The question of agency is most interesting when applied to the king’s youngest daughter. Why did she marry a poor orphan? Was it because she was the youngest, and had no dowry? Was it because he was the last bachelor left? Or did she choose to marry him for love rather than money? The answer to these questions significantly changes how we read the story. If the daughter was constrained by circumstance, she has less agency; if she chose poverty intentionally she had a great deal more. Unfortunately, the cloth itself can’t answer these questions without its storyteller.

The cloth conveys less narrative continuity (taken by itself, without a storyteller) than most written histories, but part of it is written and does the work of demarcating important events the same way written history does. In a way the cloth is in a way similar to the winter counts chronicle we looked at, in that it uses imagery to remind the history-keeper of important events. However, it does also use writing in a way the winter counts didn’t. In this way the cloths are a sort of hybrid between the chronicles and written history, but this one differs from both in one important way: it’s conveying a story, not a history.

The shaky English, the gaps in time, and the uncertainty of the characters’ motives all emphasize the fact that the story cloth was not meant to stand on its own. It cannot present the whole story without its storyteller, someone familiar with both the folk tale itself and the cultural context it came from. This is part of what makes the story cloth so powerful: because it doesn’t present the whole story on its own, it demands that the people who made it take part in the telling, and so ensures their ownership and agency over their own story and the culture it came from.

You must be logged in to post a comment.