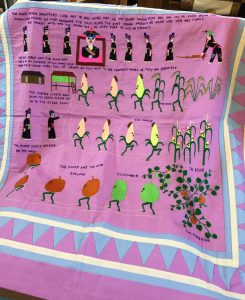

The story cloth I was examining was donated to the East Side Freedom Library in 2005 by a retired schoolteacher. The outer stripes that indicated dialect were lavender, light gray/blue, and white. The story has three distinct parts; the first tells of a king with seven daughters and how his youngest daughter, Yer, married Yao, an orphan; the second talks about crops growing in the summer; the third part is where the farmer couple (implied to be Yer and Yao) ask the ripened crops to go to the storehouse and the crops uproot themselves to fulfill the request. Daria and I were speculating that there is much more to the story, and that the cloth was a visual representation of the overall story arc, but that to tell the full story you’d probably need an oral component accompanying it. The passage of time in the story is not reported directly, only implied through the growing crops and the transition from the king’s seven daughters to the farmer couple.

In this story every living thing has agency, down to the plants. The agency of people is demonstrated by the marriage of the king’s youngest daughter. Typically we wouldn’t expect someone with royal status to marry a poor orphan, even if she was the youngest daughter and farthest down in the line of succession. But our expectations are flouted by Yer and Yao’s marriage, and the king’s line “please go find husbands for yourselves” makes it clear that this was Yer’s decision, and a demonstration of human agency. The farmer couple’s crops also display agency in their ability to make promises to the couple, and move on their own to fulfill those promises. The farmer asks the crops to go to the storehouse, and “they went to the farmer’s house as they had promised.” To do this, they uproot themselves and walk into the storehouse, giving an even clearer idea of agency. If even the crops have the agency to walk around, there’s an implication that (at least) every living thing in this story-world has equal amounts of agency to think and act for themselves.

In this story every living thing has agency, down to the plants. The agency of people is demonstrated by the marriage of the king’s youngest daughter. Typically we wouldn’t expect someone with royal status to marry a poor orphan, even if she was the youngest daughter and farthest down in the line of succession. But our expectations are flouted by Yer and Yao’s marriage, and the king’s line “please go find husbands for yourselves” makes it clear that this was Yer’s decision, and a demonstration of human agency. The farmer couple’s crops also display agency in their ability to make promises to the couple, and move on their own to fulfill those promises. The farmer asks the crops to go to the storehouse, and “they went to the farmer’s house as they had promised.” To do this, they uproot themselves and walk into the storehouse, giving an even clearer idea of agency. If even the crops have the agency to walk around, there’s an implication that (at least) every living thing in this story-world has equal amounts of agency to think and act for themselves.

To compare the story of the story cloth to other culturally important stories with fantastical elements, the story cloth’s characters are leaps and bounds ahead of characters in other stories we’ve looked at (like Bede or The Odyssey) in terms of character agency. Many other oral stories that were eventually written down that originated in the West placed a lot of emphasis on divine will; most important events were attributed directly to something a god or gods did, or the story’s hero did something because it was a god’s will. The stories are also very different in terms of their characters, although part of this could be attributed to the possible incompleteness of the story cloth. The Hmong story cloth didn’t seem to place any character into a main character role, much less the role of a hero. The story wasn’t about overcoming some great hardship and saving a land; it was a more mundane story about marriage and farming. Both forms of stories are culturally important to the people who pass them on, and I suspect their purposes are similar, but they accomplish their goals in different ways. I think the Hmong story cloths help to build a sense of community and common history, just like our predictions about stories like Beowulf. It’s most definitely not the only purpose of the story cloths, but I do think they parallel other oral storytelling forms we looked at earlier in the semester.

Irene Schulte

You must be logged in to post a comment.